‘As American as Apple Pie’

Marcia Biederman ’70 tells of a murder mystery from an era when abortion was both illegal and common

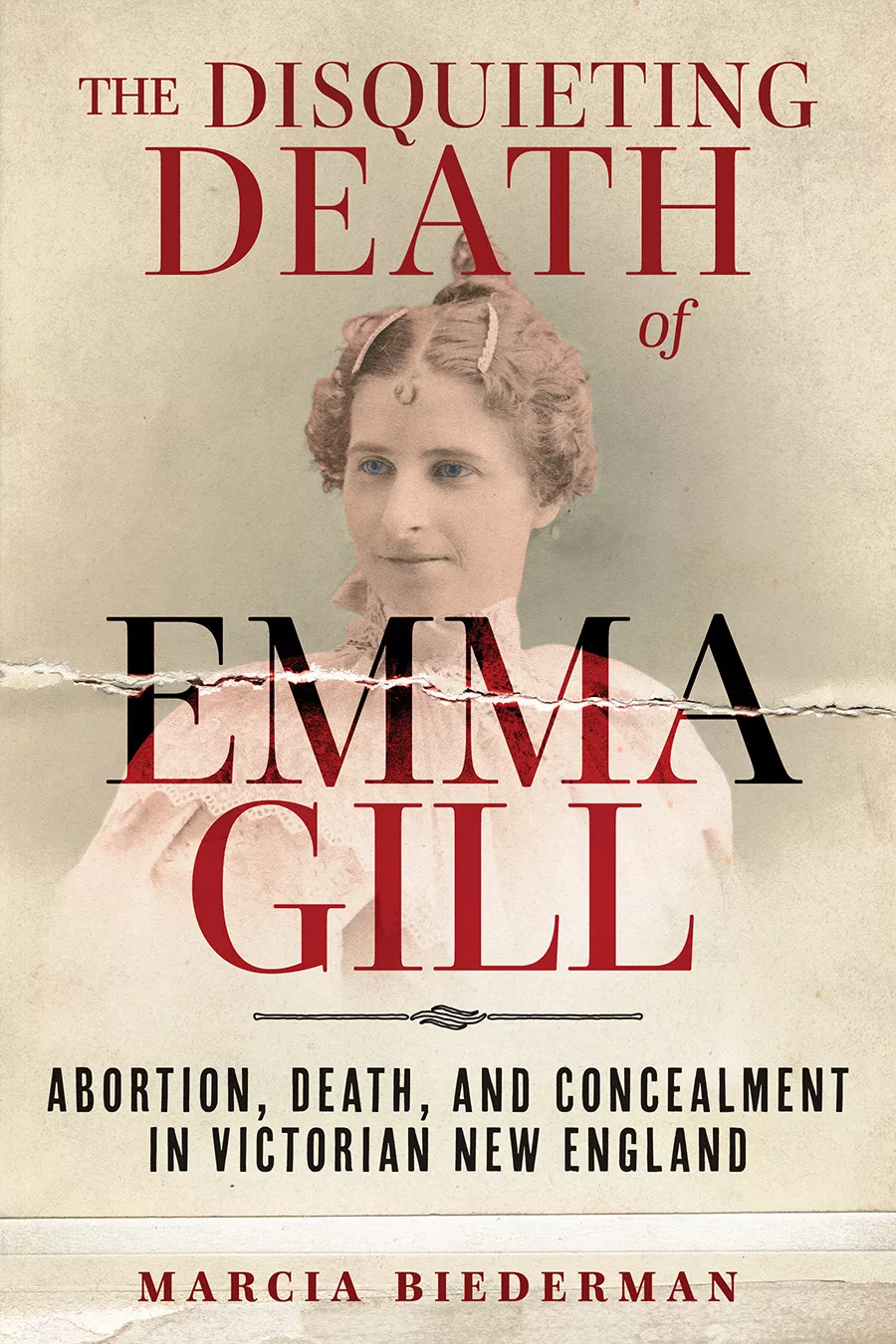

A newspapers.com search led Marcia Biederman ’70 to the scene of a 126-year-old crime. “Bridgeport Murder Mystery” screamed the headlines. In the late 19th century, when abortion was outlawed in every state yet illegal providers abounded, Emma Gill was one of many women who ended up dead. In The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill: Abortion, Death, and Concealment in Victorian New England, Biederman crafts a narrative from the discovery of Gill’s body and the trial of Nancy Guilford, who, along with her husband Henry, spent decades providing abortions in Connecticut and Massachusetts in between prison sentences. Biederman attended Bryn Mawr when abortion was illegal, so the “complicated moral landscape” of 1898 resonated with her. Her book tells how providers would run coded newspaper ads and usually escaped prosecution––unless something went terribly wrong. “The newspaper publishers would end up running the ads and covering the trials,” Biederman says. “Abortion was as American as apple pie.”

EXCERPT FROM THE DISQUIETING DEATH OF EMMA GILL, © 2024, MARCIA BIEDERMAN

Distrusting newspaper sketches, people across the nation formed their own versions of the face. A parade of parents, husbands, and lovers insisted it was their absent daughter, wife, or romantic partner. Described as “slender and graceful in figure,” the reconstructed form became an American Everywoman. Within weeks, the Bridgeport police received more than three hundred letters from people believing they knew the person she once was. Only one-third were mailed from Connecticut. Hundreds of people in dozens of places thought someone they knew might seek an illegal abortion.

The murderer was a fool to leave the face intact instead of pouring acid on it, said a Bridgeport police detective. Speculating why the body wasn’t minced more finely to hinder identification, the Medico-Legal Journal credited the “impelling force of fear,” typical in cases “in which the victim dies, not from murderous intent, but as the result of some illegal act, as rape or abortion.”

There was fear of detection, to be sure, but also the fear of separation. A daughter and her son, both embroiled in this, had been torn from their mother in childhood. As adults, both were devoted to her. There was a father—violent, philandering, and, at this critical time, imprisoned. He stood by the others, at least publicly.

They were the typical crime family of modern-day television and film, loving one another while wreaking havoc on society—except that dismembering a body wasn’t a serious crime, and many of their neighbors weren’t sure that abortion should be either.

Nancy Alice Guilford didn’t know the waters of Bridgeport, but she’d been seeing women patients there for years. Dozens of ads for Dr. Guilford listing her Bridgeport office hours had appeared in Connecticut papers and even a public-library bulletin. Naming her specialty as “diseases of women,” the ads were barely encrypted. They also gave her address: 51 Gilbert Street in the center of Bridgeport, near city hall and police headquarters.

This was no back-alley operation. A brownstone with bay windows on the second floor and dormers on the third, it was judged by the press to be a handsome dwelling. Cleaned by a live-in housekeeper, it defied the stereotypes of abortion-parlor filth and squalor in the era before Roe v. Wade. Indeed, police noted later that the hallway had a strong odor of carbolic acid, an antiseptic favored by germ-theory pioneer Joseph Lister.

When finally cornered, after a chase spanning two continents and three countries, the midwife threatened to expose the names of her four hundred Bridgeport patients, many known to the “best society,” and twice that number in New Haven, from which she’d come. She promised revelations that would shake the “pillars of the courts, the clubs, and the churches.” Or so said the newspapers, and no one doubted it.

Published on: 05/28/2024