Professor Homay King's Book on Thinking About Film, Video, and Time-Based Art

History of Art Professor Homay King’s latest book Virtual Memory: Time Based Art, and the Dream of Digitality, has just been published by Duke University Press.

The book’s publication caps off a busy year for King. In addition to finishing up the book, she was involved in the development of China: Through the Looking Glass, the recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that drew record crowds for a Costume Institute exhibition.

Virtual Memory: Time Based Art, and the Dream of Digitality, is King’s second book. In it, she looks to reframe the debate that’s been going on as we move toward a film distribution system that will be almost entirely digital.

“The primary debate has been, “Is film still film when it’s not celluloid or do we have an entirely different medium on our hands?’” explains King. “My argument in this book goes against that medium specificity. If you watch a beautifully restored digital copy of The Searchers there are differences from the celluloid version but it’s still a film.”

However King does argue for a distinction between analog and digital that is more conceptual in nature and not necessarily tied to the storage medium.

“What I call digitality is an approach to filmmaking that aspires to numerical calculability, timelessness, permanence, and transcendence,” says King. “Whereas the analog is a mode that’s associated with durational time, with things that are grounded in real physical time and space, with earthly concerns and with entropy and decay. So while these works are made on digital film, they are about the fragility of the real world rather than about some Matrixy world of ones and zeros.”

In Virtual Memory, Time Based Art, and the Dream of Digitality, King also looks to revise a previous understanding of the term “virtual.”

“When I use the term in this book it’s in a way that is at odds with the way many use it today but may actually be more in keeping with earlier interpretations of the word,” says Homay. “If I say virtual reality today most people are going to think ‘oh this is a fake reality that’s completely computer generated and simulated.’ But the word virtual only started to mean that in the 1980s. Before that, it referred to things that were immanent or on the verge of actualization. What I want to do is recover that older, more philosophical sense of the virtual and apply it to thinking about contemporary visual media.”

King became involved in the development of China: Through the Looking Glass after getting an email from the exhibition’s curator, Andrew Bolton, who had read her book Lost in Translation: Orientalism, Cinema and the Enigmatic Signifier.

“He had read my book and wanted to do an exhibition that was very much aligned with my research. The exhibition wasn’t meant to be about authentic Chinese fashion but instead about this sort of fantasy that had been created by the West,’ says King.

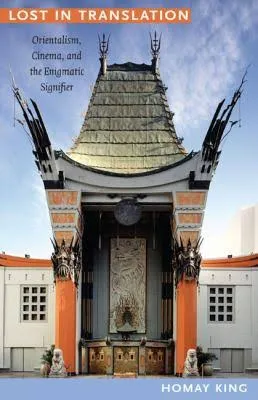

Grauman’s Chinese Theater graces the cover of King’s book and serves as a prime example of the cultural objects King studies and that were showcased at the Met through fashion.

Built in the 1920s, Grauman’s, home for so many years to the Oscars and site of the Hollywood Walk of Fame, is probably the most well-known movie theater in the world.

And as a piece of architecture, it’s pure fantasy, explains King.

“It’s called the Chinese Theater and it has a pagoda type of structure. It has these curved eaves, things that are vaguely reminiscent of a traditional Chinese aesthetic, and yet it turns out that the building’s designers actually were inspired by the Orientalist period of the furniture maker Chippendale and a movement know as Chinoiserie in Britain and France in the 18th and 19th centuries. This was actually an amalgamation of styles from throughout the Far East fused together to create a fictional, imaginary fantasy world.”

In addition to providing support in the development of the exhibition, King also contributed an essay to the exhibition catalog, “Cinema’s Virtual Chinas.”

King started at Bryn Mawr in 2002 and helped found the Program in Film Studies in 2005.

Interest in the program has been consistently strong. On average 8-10 students graduate with a minor in film studies and there are several independent majors each year.

The program offers both production and theory courses and there’s typically about a 50/50 split between students who want to enter the film industry and video production and those interested in the academic study of film. A number of students from the program have gone on to earn an MFA or Ph.D., with one student going on to a film preservation program.