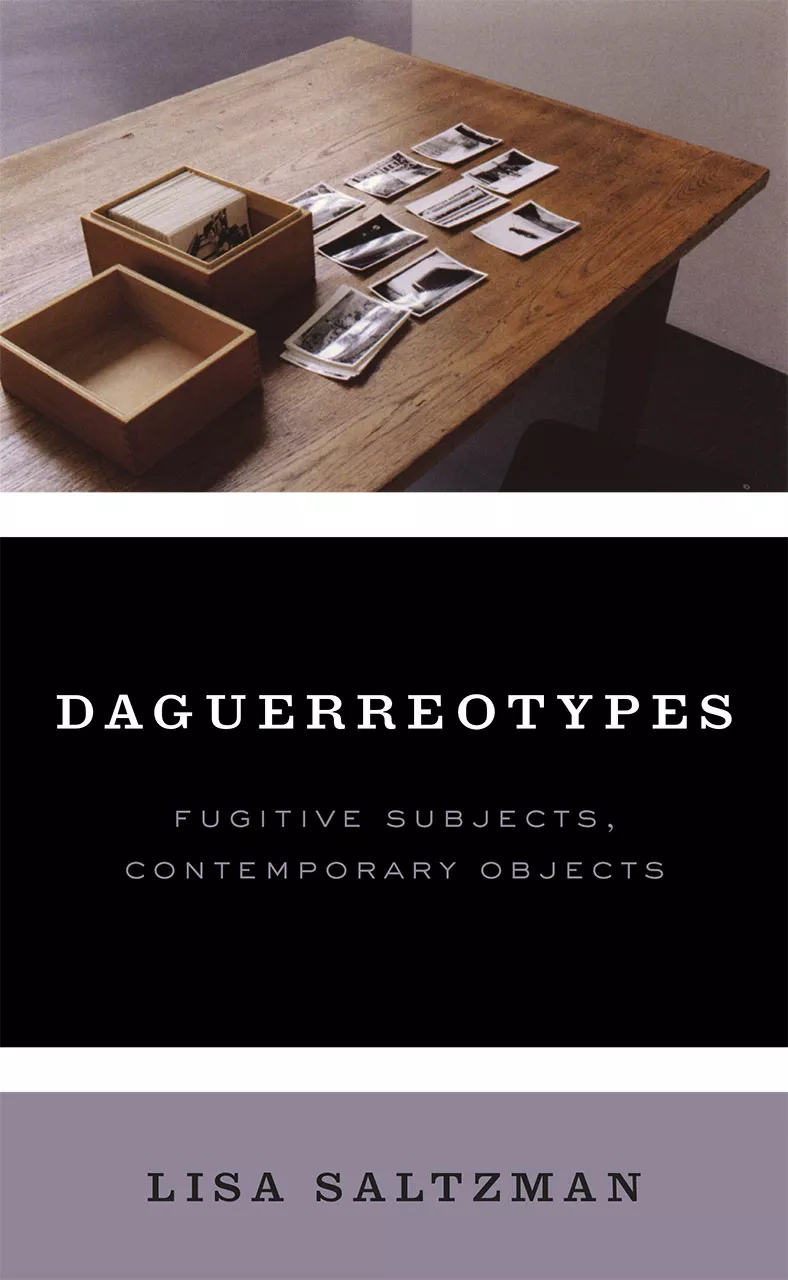

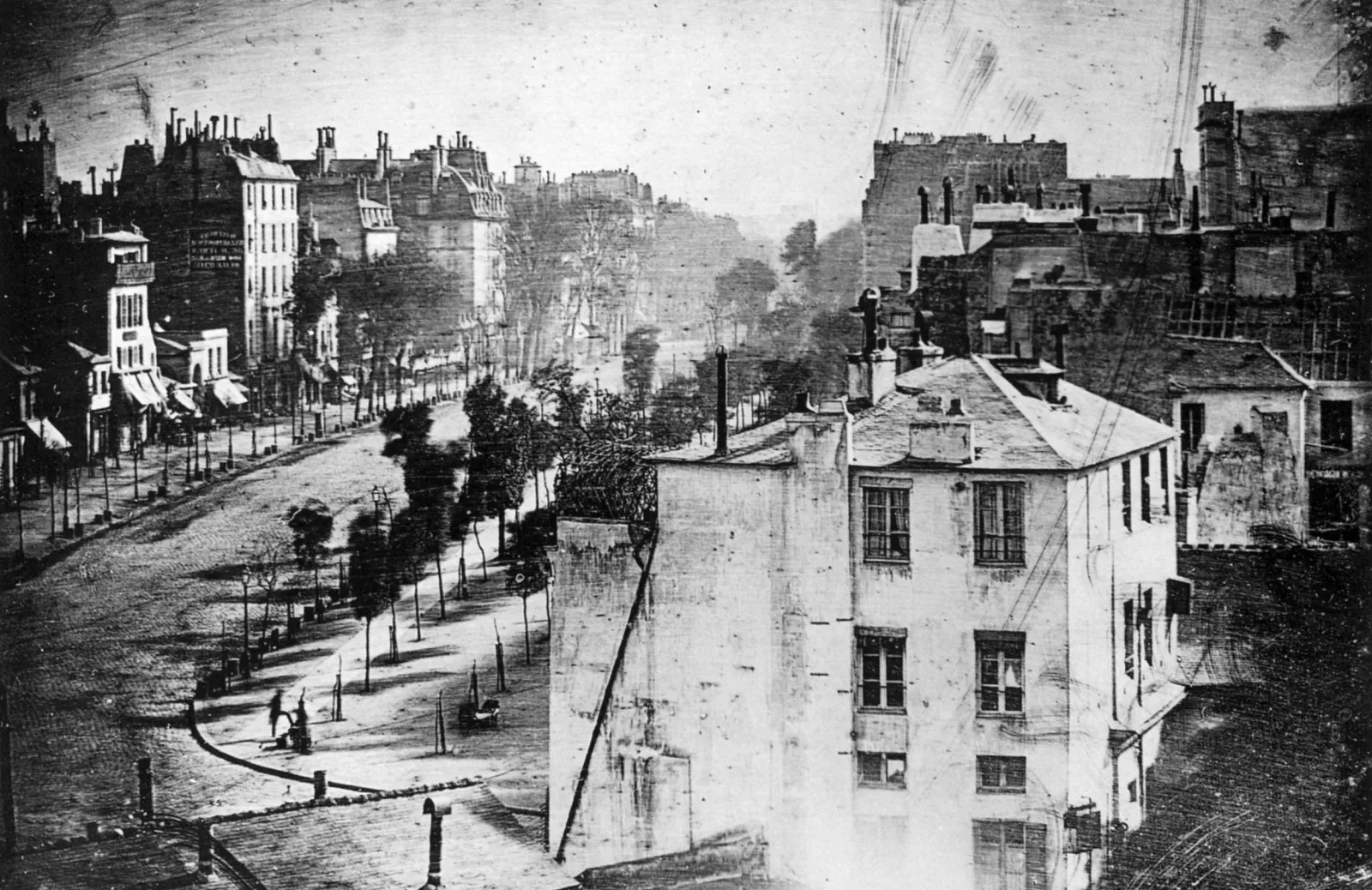

History of Art Professor Lisa Saltzman begins her new book, Daguerreotypes: Fugitive Subjects, Contemporary Objects, with a historical event from three centuries before the invention of photography: the celebrated 16th century case of the French peasant Martin Guerre. This story of imposture and mistaken identity might seem an unlikely point of departure for a book that contemplates the changing role of photography in contemporary visual culture; but Daguerreotypes, whose title plays on both his name and that of the inventor of the very first form of the photograph, pops with connections among far-flung areas of inquiry.

The fantastic story of Guerre, whose return home after many years’ absence helped convict the man living in his stead, is suffused with issues of identity and raises fundamental questions about identification that would later be answered by the invention of photography. As Saltzman puts it: “Who’s real, and who’s the impostor? Who’s the original, and who’s the copy? Without a photograph, or so many would claim or imagine, no one knows for sure.”

In the Introduction of Daguerreotypes alone, Saltzman segues from the case of Guerre to Ridley Scott’s science fiction film, Blade Runner—a tale that hinges on human “copies,” or replicants, and their poignant reliance on photographs for evidence of their identities. Both Blade Runner and the film The Return of Martin Guerre came out in the early 1980’s, a moment that Saltzman argues marks a pivotal shift in the understanding of photography, from its status as a cultural icon of the modern documentary tradition to a more ambiguous, postmodern, aesthetic object.

Daguerreotypes, published in July by University of Chicago Press, is Saltzman’s third book. In some ways it continues the exploration of the role of history and memory in contemporary art she explored in Anselm Kiefer and Art after Auschwitz and Making Memory Matter: Strategies of Remembrance in Contemporary Art. But it’s also a departure, venturing into the field of photography, which has its own developed body of theory and criticism.

The book aims to follow what Saltzman calls the “afterlife” of photography: the idea that in this digital age photography has been "displaced as a tool of identification by genetics and biometrics and dematerialized and dispersed as a document into the virtual archives of data centers and social networks.”

“We have moved past the time when a photograph stood as the authoritative chemical trace of a particular place and time,” says Saltzman. “And we must now confront photography under the competing signs of ubiquity and obsolescence.”

“Introducing the concept of the medium’s afterlife is enormously useful,” notes University of Minnesota Art Historian Jane Blocker, as it helps us “reconsider the notion that photography is dead.”

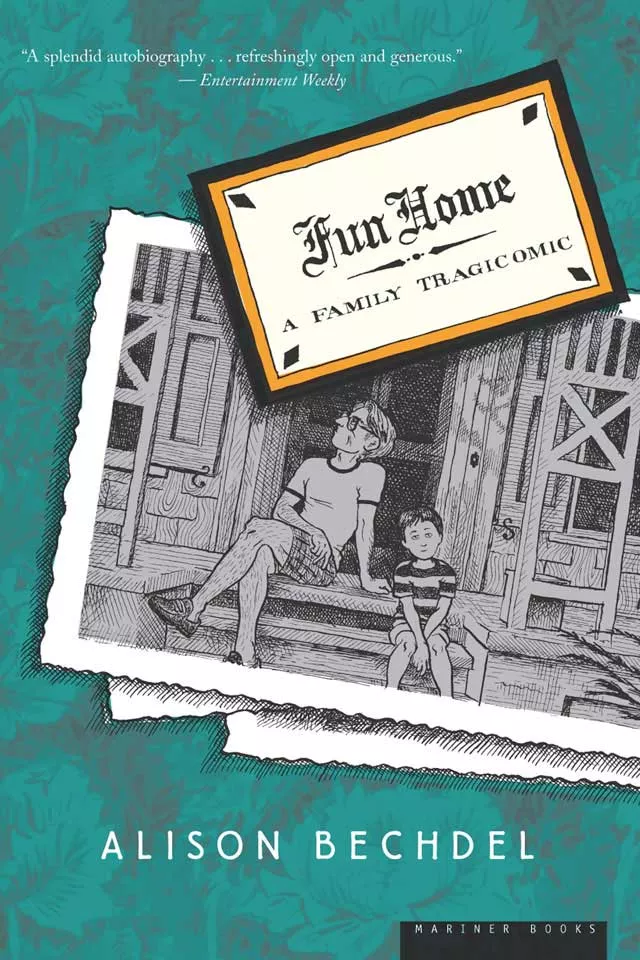

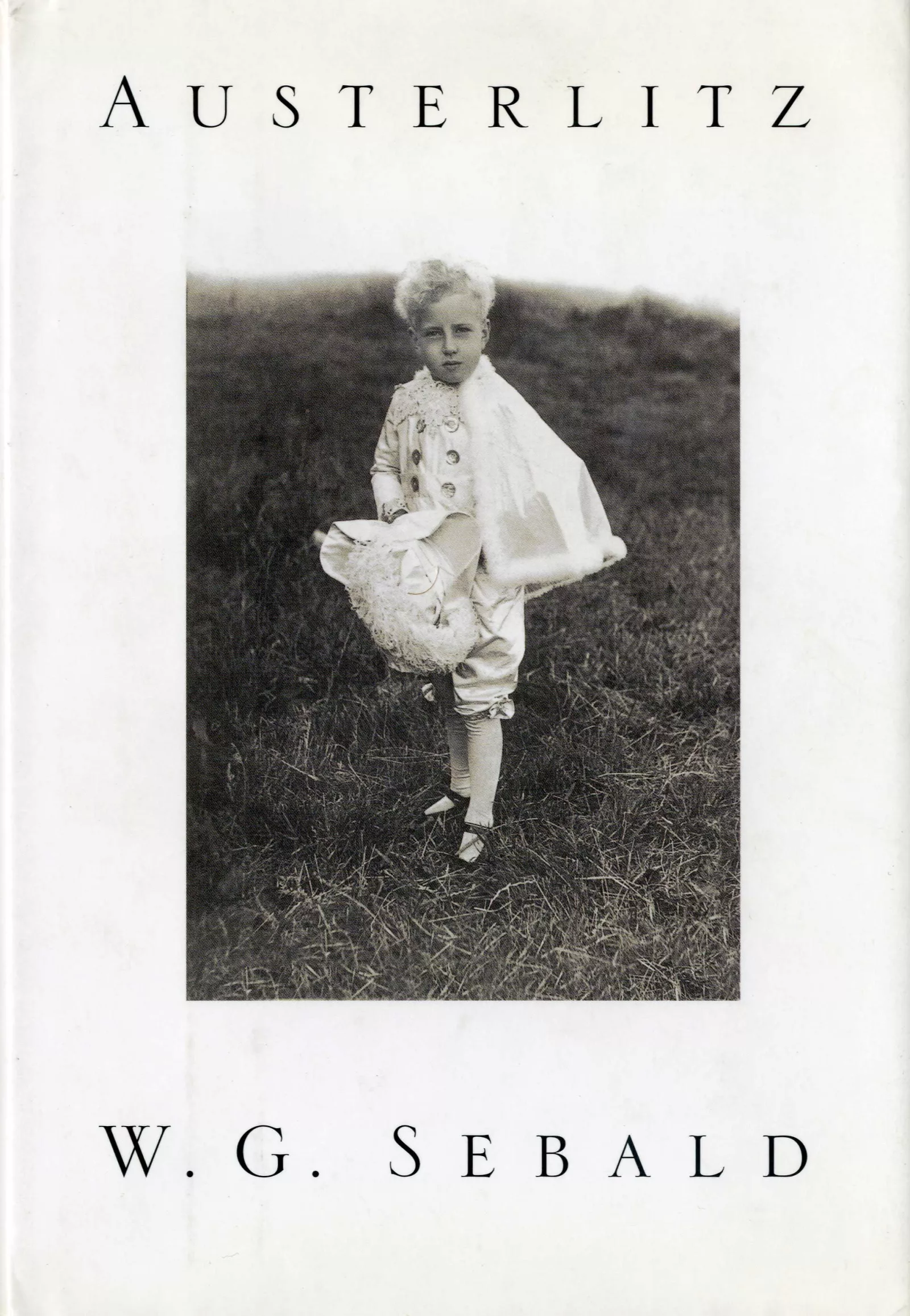

Among the works Saltzman examines in Daguerreotypes that adaptively reuse photography, digitally or otherwise, are Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home and W. G. Sebald’s hybrid novel Austerlitz.

In Fun Home, Bechdel points up the subjectivity and ambiguity of old family snapshots by re-drawing them instead of reproducing them. In Saltzman’s reading, this allows the author/artist to embody the malleability of her own memories, particularly those of her late father, as tantalizingly suggestive yet equivocal as the pictures themselves.

As Saltzman writes:

“Neither elegy nor eulogy, Fun Home is an ambivalent homage to an absent and elusive father…Mining whatever materials she can find to reconstruct an

account of growing up in a household in which the nature of her parents’ relationship was, as for any child, deeply enigmatic, Bechdel produces a recursive story that reveals both what she has come to find and remember about her father and how those discoveries and realizations inflect and inform her sense of self… Recreated as and in drawings, with all the subjectivity, intimacy, and fallibility of the handmade mark, even as these images forsake the evidentiary object for the avowedly personal testimony of the drawing, they manage to lay claim to something of photography’s legacy as objective record.”

Austerlitz, the story of a man struggling to remember and reclaim his forgotten childhood in 1930s Prague, broke ground with its provocative use of actual photographs to illustrate a fictional character’s life.

“Exiles and émigrés all, the subjects of Sebald’s literary imagination reach for photographs as if for moorings,” writes Saltzman. “And yet, the subjects of Sebald’s fictional histories and historical fictions experience themselves as not so much anchored by the photographs that accompany their stories as cut

adrift. For Austerlitz, the central character of the novel that bears his name, it is the stories that surround a photograph of himself as a child that undo, rather than secure, his identity. His life, saved and shaped by events that he only belatedly and dimly remembers, has been a fiction, even if lived and experienced as his only reality. He is and is not the child he knew himself to be. But he also is and is not the child he learns he was. He has what comes to function as a lost twin, a double whose image is preserved in a photograph but whose identity he cannot fully assimilate as his own. One might say, he is his own Martin Guerre.”

The emergence in contemporary art photography of often large-scale, staged works by artists including Jeff Wall, Gregory Crewdson, An-My Lê, and others is also examined in Daguerreotypes. Saltzman coins the term “retro-spectacles” for their work—which makes photography into a zone of theater, of tableaux, a contemporary form of that age-old tradition, practiced by artists from Rubens to David and Delacroix, history painting.

Saltzman did much of the writing with the support of a Guggenheim Fellowship, and during a fellowship year at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. The seed that would become Daguerreotypes grew out of a Graduate Group interdisciplinary seminar called History and Memory, which Saltzman co-taught with her colleague Madhavi Kale, a professor in the Bryn Mawr Department of History. It was Kale who wanted to include The Return of Martin Guerre, a field-defining book by the medieval historian Natalie Zemon Davis and the basis for the film, in the syllabus. Kale and Saltzman’s conversations about that book touched playfully on its uncanny resonances with the history of photography, and the two colleagues joked that they should write a book about these ideas.

The following summer, Saltzman wrote what would become the book’s first ten pages. “It had stuck with me,” she recalls. “And I gave it to [Madhavi] to read, and I said, ‘What do you think of this? Do you want to do a book?’ And she said, ‘No, but you do.’”

Fellow art historian Andrés Zervigón, on the faculty at Rutgers, has called Daguerreotypes “a superbly insightful investigation,” offering “an alternative history and critique of photography.” Blocker of the University of Minnesota notes Saltzman’s “more personal, contemplative voice,” in contrast to the “the more dry and objective language that might be found in other art historical scholarship.”

Now, with smartphones and instant photo-editing software, we’ve all become photographers, awash in an ocean of images, and increasingly aware of photography’s ability to edit and present reality in certain ways. Saltzman herself doesn’t use any form of social media, but is willing to jump in and consider, for example, the parallels between the disappearing images of Snapchat, and the pre-photographic period when images were captured, only to evaporate without chemical fixatives. She views the deluge of photographic sharing on the Internet as “another instance of the hold that photographs have on our imagination. Nothing taps into sentiment the way a photograph does. No matter what we know about the staging and manipulation of photographs, even in the decades right after the invention of the medium,” she continues, “we also still believe in them… There’s an affective and evidentiary dimension to the photograph that’s unparalleled in the arts.” Saltzman’s fearless speculations shine unexpected light on the new territory we find ourselves in now.

Saltzman is Chair and Professor of History of Art and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Chair in the Humanities. She teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in modern and contemporary art and theory.